A recent study saw researchers associated with Cellvie demonstrate significant improvements to mitochondria and muscle function in aged mice by injecting additional mitochondria [1].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a reason we age

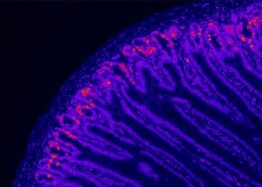

Mitochondria are cellular powerhouses that convert nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a form of energy that powers cells. It is not an exaggeration to say that without mitochondria, complex life, such as people, would not be possible.

With aging, the mitochondria can become damaged and less efficient over time. This is because producing energy is a dirty business that creates harmful byproducts called free radicals.

These free radicals bounce around inside of cells, damaging things that they strike, particularly mitochondrial DNA. This damage causes mutations, which make energy production less efficient and cause mitochondria to behave in harmful ways.

Mitochondria do not have an efficient DNA repair system like cells’ nuclear DNA. As time passes, the number of mutations in mitochondria increases. This leads to a downward spiral in which mitochondria become increasingly unable to produce energy and function properly.

A number of researchers are now developing therapies to combat this. If they are successful, it may be possible to slow down or even reverse aging in our cells.

Rejuvenating old cells with donated mitochondria

It has been known for some time that mitochondria can transfer between cells and can be absorbed into cells from their environment. This suggests transferring healthy mitochondria to an aged animal or person may be a viable approach for rejuvenation.

This is exactly what the researchers in this new study did. It is interesting that the mitochondria were harvested from mice of the same age and not younger donors.

The mitochondria were separated from the donor tissue and given directly to the test group mice. The animals were then injected directly into the hindleg muscle tissue, meaning delivery was relatively simple.

Compared to the control group, the test group saw improvements to mitochondrial function and muscle function. There was also an improvement in endurance.

Results: The results indicated significant increases (ranging between ~36% and ~65%) in basal cytochrome c oxidase and citrate synthase activity as well as ATP levels in mice receiving mitochondrial transplantation relative to the placebo. Moreover, there were significant increases (approx. two-fold) in protein expression of mitochondrial markers in both glycolytic and oxidative muscles. These enhancements in the muscle translated to significant improvements in exercise tolerance.

A follow-up study to better understand these results

As mentioned, the notable thing about this particular study was that even though the mitochondria were delivered from animals of the same age, the results demonstrate some level of improvement.

Perhaps there is some form of dilution of damaged mitochondria happening here that explains the results. The influx of additional mitochondria may be somewhat offsetting the burden of mutated mitochondria in the recipient.

That said, it is reasonable to assume that delivering mitochondria from a younger donor would be more advantageous. It would make for an ideal follow up experiment using mitochondria harvested from younger animals.

There is also the consideration of if mitochondrial haplotypes need to match between donor and recipient or not. Mitochondrial haplotypes refer to groups of closely linked genetic markers present on mitochondrial DNA. These haplotypes are used to trace maternal lineages and genetic variations in populations.

Understanding the role of haplotypes in a follow-up study would also be beneficial. If they do not need to match to be effective, that would also simplify production at scale.

An inroad for rejuvenation research

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of aging, but it’s unlikely that “aging” will be the target of this research. Companies working on mitochondrial transfer will probably initially target frailty and muscle loss in older adults for clinical trials. Once approved, the approach could be used off label for other related conditions and aspects of aging.

The great news is that growing mitochondria in culture is likely a scalable technology. This is very important and directly relates to the ability of people to access and afford therapies.

Many rejuvenation biotechnology supporters are worried about being able to access it in the future. After all, it’s no use if a therapy works but is unaffordable for most people. Hopefully, companies such as Cellvie and Mitrix will use bioreactor-grown mitochondria to cost-effectively produce them en masse.

It’s likely that medical tourism in countries with less regulations will offer mitochondrial transplants to those with the means. Obviously, those first adopters need to consider the risks of doing so. Meanwhile, the rest of us will be waiting for therapies to get through the clinic via the FDA, EMA, etc.

This avenue of research looks promising if the challenges of manufacturing at scale and access can be overcome. We will continue to follow research progress closely and hopefully will have more to report in the near future.

Literature

[1] Arroum, T., Hish, G. A., Burghardt, K. J., McCully, J. D., Hüttemann, M., & Malek, M. H. (2024). Mitochondrial Transplantation’s Role in Rodent Skeletal Muscle Bioenergetics: Recharging the Engine of Aging. Biomolecules, 14(4), 493.