Scientists from the Longevity Research Institute (LRI), which was formed by the merger of SENS Research Foundation and Lifespan.io, have achieved expression of an essential mitochondrial gene in the nucleus and proper functioning of the protein. This could pave the way for curing diseases caused by mitochondrial mutations [1].

The fragile mitochondrial DNA

The prevailing scientific consensus is that mitochondria were once independent microorganisms that entered a symbiotic relationship with larger cells. This duo gave rise to eukaryotic cells: the building blocks of all multicellular life. Without that fateful “marriage,” complex life would not exist, as mitochondria provide cells with essential energy via oxidative phosphorylation.

Over the millennia, mitochondria have retained their own DNA. However, this mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has several vulnerabilities: it lacks the protective proteins that nuclear DNA is wrapped around (histones), has fewer repair mechanisms compared to nuclear DNA, and exists in a harsh environment of oxidative stress generated by its own metabolic activity.

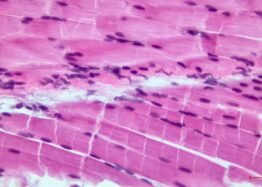

The fragility of mtDNA might have contributed to the relocation of most of its genes to nuclear DNA. Proteins encoded by those genes are synthesized in the cytosol and transported across the cell into mitochondria via a highly regulated process. However, 13 essential proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation remain encoded by mtDNA and still suffer from the same vulnerabilities. This makes mtDNA prone to mutations, particularly as we age.

Mutations in mtDNA contribute to a range of diseases, such as Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), and are linked to a wide range of age-related pathologies, including sarcopenia and Alzheimer’s disease [2]. Addressing problems caused by mtDNA mutations is a major challenge in biomedical research. However, in this study, LRI researchers have achieved a significant breakthrough by successfully relocating a mitochondrial gene to the nucleus in vivo.

Overcoming the challenges

Previously, the same team had achieved promising results in vitro [3], but finding a suitable animal model proved difficult: mtDNA genes are so essential that mutations in them usually render mice non-viable. However, a particular strand of mice exists that harbors a relatively benign mutation in ATP8, a gene encoding a subunit of the ATP synthase complex, which causes only a mildly pathologic phenotype. Alongside those mutants, wild-type mice were used as controls.

The team synthesized a nuclear-compatible version of ATP8 and inserted it into the ROSA26 locus, a well-characterized “safe harbor” site in the mouse genome. This locus is widely used in genetic engineering because it allows stable organism-wide expression of inserted genes without interfering with other essential genomic functions.

The researchers had to overcome significant technical challenges to achieve nuclear expression of a gene that is normally expressed in mitochondria (allotopic expression) and to make the protein transferrable to mitochondria. For instance, they found that efficient allotopic expression requires codon optimization: altering the DNA sequence of a gene using codons that are more efficiently translated by ribosomes.

Efficient, persistent, non-immunogenic

Eventually, their efforts paid off: allotopic ATP8 was able to compete with mitochondrial ATP8 even in wild-type mice and outperformed the mutant ATP8. The allotopic gene was expressed in all the tissues that the researchers tested, and the protein successfully integrated into the mitochondrial machinery.

“The key question was ‘How well can an allotopic protein compete with pre-existing protein?’” said Dr. Amutha Boominathan, Assistant Professor and Principal Investigator at LRI and the study’s leading author. “One fundamental concept in the field is that mitochondrial DNA exists because proteins need to be synthesized on demand for easier incorporation into their respective complexes.”

“For allotopic expression to succeed,” she explained, “you must demonstrate that protein coming from the nuclear side can be incorporated with similar efficiency. In wild-type mice, we see equal efficiency between endogenous and exogenous proteins. In our mutant model, we see increasing incorporation over time, suggesting the nuclear protein actually outcompetes the mutated one from a stability perspective.”

Importantly, the allotopic gene functioned well in the genetically modified mice’s offspring for at least four generations, with no adverse effects on fertility. While mtDNA can sometimes trigger an immune reaction when released into the cytoplasm, this gene was also well-tolerated by the immune system, as confirmed by cytokine array analysis.

A blueprint for the future

In the paper, the researchers note that their successful proof of concept does not necessarily apply to all mtDNA genes, and many challenges lie ahead. However, Boominathan is optimistic: “This provides a platform for testing other genes. With appropriate engineering we can overcome all the challenges. We’ve proven it for one protein and have promising data for others. What we’ve demonstrated here is the feasibility of expressing mitochondrial genes in a whole-body context. The inheritance patterns and lack of immune response are particularly encouraging for therapeutic applications.”

There are over 250 mitochondrial DNA diseases that could potentially benefit from this approach, according to Boominathan. “If we can achieve allotopic expression for all 13 genes,” she said, “we’d have a pathway to treat many of these rare diseases.”

The aging connection

LHON, one of the diseases that the researchers are after, “is actually an aging disorder,” Boominathan explained. “While the mutation is inherited, it specifically affects males over 40. These mutations amplify with age, particularly in tissues with high oxidative phosphorylation demands, like retinal ganglion cells. Symptoms only appear when the mutation load reaches a certain threshold.”

This is particularly relevant to post-mitotic cells that form the brain, skeletal muscle, and cardiac tissue since those cells cannot dilute mutations through cell division. “While internal recycling mechanisms like mitophagy exist, they decline with age,” said Boominathan. “If you inherit a mutation or acquire one early in life, it amplifies over time as mitophagy decreases, and these mutations often have an advantage that helps them take over.”

A three-pronged approach

“This work represents the culmination of more than a decade’s worth of effort to provide a genetic backup system for mitochondrial DNA in mammals, for which inherited mutations cause disease in nearly 1 in 200 people,” said Dr. E. Lillian Fishman, Director of Research and Education at LRI, about the study. “I am proud of Dr. Boominathan and her team’s persistence to rise to meet this technically challenging proof-of-concept that paves the way for the treatment of debilitating mitochondrial diseases like Leigh’s syndrome and progressive diseases of aging.”

This study was done as part of MitoSENS, a wider LRI project that includes a three-pronged approach to mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition to allogenic mtDNA expression, the researchers pursue boosting mitophagy with small molecules and de novo synthesis of healthy mtDNA for transfer into exogenous mitochondria, followed by introduction into cells.

Literature

[1] Begelman, D. V., Dixit, B., Truong, C., King, C. D., Watson, M. A., Schilling, B., … & Boominathan, A. (2024). Exogenous Expression of ATP8, a Mitochondrial Encoded Protein, From the Nucleus In Vivo. Molecular Therapy Methods & Clinical Development.

[2] Zhunina, O. A., Yabbarov, N. G., Grechko, A. V., Yet, S. F., Sobenin, I. A., & Orekhov, A. N. (2020). Neurodegenerative diseases associated with mitochondrial DNA mutations. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 26(1), 103-109.

[3] Boominathan, A., Vanhoozer, S., Basisty, N., Powers, K., Crampton, A. L., Wang, X., … & O’Connor, M. S. (2016). Stable nuclear expression of ATP8 and ATP6 genes rescues a mtDNA Complex V null mutant. Nucleic acids research, 44(19), 9342-9357.