A new study dives into a human-derived probiotic cocktail meant to protect against Alzheimer’s disease. The treatment improves gut health and reduces inflammation in mice [1].

The earlier, the better

Early interventions to prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease might be a more feasible approach than reversing the disease when it is fully developed. However, such preventative treatments would need to be easy to adhere to and have good safety profiles, as it is likely that they would require long-term use.

The authors of this paper aimed to create such an intervention by targeting the gut-brain connection, focusing on how gut microbes impact the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

From gut to brain

Microbes that live in the human gut are collectively called gut microbiota. Gut microbes are essential for human health, including brain health.

To introduce their paper, the authors discussed the connections between Alzheimer’s disease and gut microbes. Previous research has found that the gut microbiota composition of patients with Alzheimer’s disease differs from that of healthy people [2]. What’s more, it appears that gut microbiota can play an important role in Alzheimer’s disease progression, as transplantation of an abnormal gut microbiome to healthy rodents results in the development of Alzheimer’s symptoms [3].

Therefore, the researchers decided to see how well probiotics could work as a therapeutic strategy. They used a human-origin probiotics cocktail consisting of five Lactobacillus and five Enterococcus strains that had previously been linked to reducing gut permeability and inflammation [4].

A cocktail for Alzheimer’s

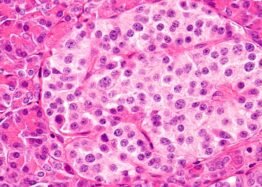

The researchers used APP/PS1 mice, which are genetically modified to express human amyloid-β (Aβ). These mice develop signs of Alzheimer’s disease as the Aβ accumulates, and their cognitive abilities decrease earlier than those of wild-type mice.

In this experiment, 6- to 8-week-old APP/PS1 mice received a human-origin probiotic cocktail for 16 weeks. This treatment led to decreased Aβ accumulation in the hippocampal region of the brain, which is the first region where Alzheimer’s disease changes manifest, and mitigated the mice’s cognitive decline compared to untreated controls, suggesting that the treatment protected against the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Reduced inflammation

Apart from Aβ plaques, Alzheimer’s disease is also linked to neuroinflammation. Studies even suggest that systemic inflammation in mid-life can promote cognitive decline even 20 years later [5].

After giving their probiotic cocktail to mice, the researchers observed reduced neuroinflammation, decreased activation of the brain’s immune cells (microglia), and improved integrity of the blood-brain barrier, which regulates the entry of molecules and substances from blood to the brain. Systemic and gut inflammation were also reduced compared to controls, as measured by inflammatory markers in the blood and gut.

Better gut health

Probiotics seemed to have a broad positive impact on the gut that extended beyond inflammation. Testing of multiple markers of gut health showed improvements in the probiotic-treated animals compared to the control mice, such as reductions in gut permeability and structural and functional improvements to the linings of both the large and small intestines (intestinal epithelia). The researchers believe that the effectiveness of their probiotics cocktail is likely to be due to these improvements in intestinal barrier integrity.

As expected, the probiotic treatment had significant effects on the gut microbiomes of the treated mice. While this treatment didn’t impact microbial diversity, it affected the abundance of different microbial populations, increasing the numbers of beneficial microbes.

Males benefit more from probiotics

The risks of Alzheimer’s disease development and progression differ by sex. Therefore, the researchers examined differences between the data that they obtained from male and female mice.

They noted that while cognitive performance and reduction in Aβ were observed in both sexes, males had slightly better results than females. This was due to the fact that some, but not all, of the molecular mechanisms that provide such cognitive benefits differ between males and females.

The impact of probiotic treatment on microglial activation and inflammation was similar in male and female mice, except for one of the inflammatory markers in the brain (Il-1β), which was significantly reduced in male but not in female mice.

However, the researchers noted several positive changes in gut permeability, blood-brain barrier, and inflammation that were observed only in male mice but not females. They also noted that probiotic treatment had different impacts on the microbiomes of male and female mice.

Gut-brain connection

The researchers discussed possible mechanisms, looking at both previous research and their own results. They believe that an imbalance in gut microbes, specifically an increase in microbes associated with inflammation, leads to local gut inflammation that causes gut leakiness. This leads to a leakage of pro-inflammatory molecules into the blood, resulting in systemic inflammation that ultimately reaches the brain.

These pro-inflammatory molecules can harm the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, which allows them to infiltrate the brain and activate the brain immune system (microglia), leading to neuroinflammation. The researchers hold that this cascade from the gut to the brain contributes to the accumulation of Aβ and results in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

[Probiotic treatment] suppresses the origin of inflammation from the gut by preventing gut permeability, thereby keeping systemic inflammation in check. This, in turn, preserves the function of the BBB, preventing pro-inflammatory burdens on the brain and maintaining control over microglia activation, neuroinflammation, Aβ accumulation. Ultimately, this helps preserve cognitive health and protect against AD progression.

While this study shows a possible mechanism of the connection between the gut-brain axis and Alzheimer’s disease and provides supporting evidence, it still needs more data to prove that the proposed mechanism is correct. Further experiments and studies in different models of Alzheimer’s disease could enrich and support these conclusions, and safety and efficacy would need to be examined in human beings.

Literature

[1] Prajapati, S. K., Wang, S., Mishra, S. P., Jain, S., & Yadav, H. (2025). Protection of Alzheimer’s disease progression by a human-origin probiotics cocktail. Scientific reports, 15(1), 1589.

[2] Vogt, N. M., Kerby, R. L., Dill-McFarland, K. A., Harding, S. J., Merluzzi, A. P., Johnson, S. C., Carlsson, C. M., Asthana, S., Zetterberg, H., Blennow, K., Bendlin, B. B., & Rey, F. E. (2017). Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific reports, 7(1), 13537.

[3] Grabrucker, S., Marizzoni, M., Silajdžić, E., Lopizzo, N., Mombelli, E., Nicolas, S., Dohm-Hansen, S., Scassellati, C., Moretti, D. V., Rosa, M., Hoffmann, K., Cryan, J. F., O’Leary, O. F., English, J. A., Lavelle, A., O’Neill, C., Thuret, S., Cattaneo, A., & Nolan, Y. M. (2023). Microbiota from Alzheimer’s patients induce deficits in cognition and hippocampal neurogenesis. Brain : a journal of neurology, 146(12), 4916–4934.

[4] Ahmadi, S., Wang, S., Nagpal, R., Wang, B., Jain, S., Razazan, A., Mishra, S. P., Zhu, X., Wang, Z., Kavanagh, K., & Yadav, H. (2020). A human-origin probiotic cocktail ameliorates aging-related leaky gut and inflammation via modulating the microbiota/taurine/tight junction axis. JCI insight, 5(9), e132055.

[5] Walker, K. A., Gottesman, R. F., Wu, A., Knopman, D. S., Gross, A. L., Mosley, T. H., Jr, Selvin, E., & Windham, B. G. (2019). Systemic inflammation during midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: The ARIC Study. Neurology, 92(11), e1256–e1267.